Transcript of Episode #204 of the OEITH podcast, Depressive Hedonia, exploring a form of depression first identified by Mark Fisher, its dynamics, the challenges it poses to magical practice, and a possible antidote discovered through the tarot.

In one of the Pali suttas, the one known as the Brahmajāla Sutta, the Buddha mentions the following: “Some ascetics and brahmins,” he says,

remain addicted to attending such shows as dancing, singing, music, displays, recitations, hand-music, cymbals and drums, fairy shows […] combats of elephants, buffaloes, bulls, rams […] maneuvers, military parades […] disputation and debate, rubbing the body with shampoos and cosmetics, bracelets, headbands, fancy sticks […] unedifying conversation about kings, robbers, ministers, armies, dangers, wars, food, drink, clothes […] heroes, speculation about land and sea, talk of being and non-being… (cited in Maté 2018: 213)

So, even back in the far-flung, ancient world of the Buddha there was no shortage of things and activities to distract us, to draw us in. And this passage from the suttas is one that Gabor Maté includes in his book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts (2018), which is an exploration of addiction.

Maté suggests that if the buddha was teaching today, maybe some of the things he might have included on that list would be: sugar, caffeine, talk shows, gourmet cooking, right or left-wing politics, aerobic exercise, crossword puzzles, meditation, religion, gardening, golf… The point that Maté extracts from all of this is the following. He says:

In the final analysis, it’s not the activity or object itself that defines an addiction but our relationship to whatever is the external focus of our attention or behaviour. (Maté 2018: 213-4)

In other words, what he’s saying there is probably what the Buddha was also saying, which is that it’s possible to get addicted to absolutely anything. Anything that gives us some modicum of pleasure has the potential to be engaged with in the form of a relationship where whatever this thing is, it begins to assume the status of something that we feel that we cannot do without. We find ourselves turning to it as a retreat from unhappiness or distress that we might be feeling in other parts of our lives. These things may not be worthy of the attention that we find ourselves feeding into them. That’s certainly what the Buddha was highlighting, and what I’m going to try and talk about in this episode is perhaps one of the greatest enemies to our magical practice, our spiritual practice – whatever that happens to be.

The words that the Buddha used to describe it get translated into English as things like “sloth” and “torpor”. Other words used for it are things like: “lack of motivation”; “languishing”; the French word ennui; “nihilism”; “apathy”. It’s something quite nebulous to describe, quite difficult to get hold of and – for something that takes the form of such a deadening, blank feeling – it’s remarkably nuanced. But the name for it that I’m going to adopt as my reference point is one that was coined by the late political writer, Mark Fisher, who called it “depressive hedonia”.

A kind of paradox. A kind of oxymoron. “Hedonia”, of course, is the source of the word “hedonism”. “Hedonia” means “pleasure”, “enjoyment”, and there’s also its opposite, “anhedonia”, which refers to states in which it’s impossible to gain pleasure or enjoyment. “Depression,” writes Fisher,

is usually characterized as a state of anhedonia, but the condition I’m referring to is constituted not by an inability to get pleasure so much as by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure. (Fisher 2009: 22)

What Fisher is describing there is a feeling, an emotional situation, which is a tormenting mix of needing something, of wanting something, of taking a fix from something, and having that thing close at hand, having it available, yet that feeling of needing a fix never, ever entirely goes away, and I think this is a feeling that many of us have become more and more familiar with.

I’m thinking of things like scrolling through social media: that sensation we can have that we’re gaining from it some kind of distraction, but a kind of distraction that remains as a distraction and never really tips over into providing enjoyment.

Fisher encountered this state of mind in the students that he was teaching: sixteen to eighteen year-olds. Teenagers. One example he gives is of a boy who was wearing headphones in class. So, Fisher challenged him and the student’s response was that it didn’t matter that he was wearing headphones because he wasn’t playing any music through them. And then, another time, the same student’s headphones were lying on the desk and, very faintly, music was coming through them. Fisher asked him to turn it off, and the boy’s response was: “Well, what’s the point in turning it off?” because even he (who was sitting closest to the headphones) couldn’t hear the music because it was on so low.

The conclusion Fisher drew from this is that there’s something here about finding ourselves drawn into relationship to things because they hold the promise of fulfilment and connection rather than delivering that. The boy, it seemed, felt compelled to wear the headphones, to have them on the desk, not because they enabled him to listen to music that he liked, but because they just seemed to comfort him with the possibility that he could do that, or could have that.

These are states of mind that can exert great power over us. They have the potential to destroy our motivation, to distract us away from our true will; take us away from what we might consciously want for ourselves and lead us into these blank, numb spaces where our concentration is dissipated away by something that doesn’t even fulfil us, but often only promises to do so, or does so only partially. This state of mind, it has mixed elements: on the one hand (as we’ve seen so far) it has an addictive element to it. But there’s a depressive element here as well. At the same time, I think, there’s something here that’s about loss.

When we’re scrolling through social media, maybe we’re looking for something maybe that we feel is missing and Mark Fisher’s student with the headphones: perhaps a sense there that he needed those headphones to be present to give him a sense of connection with something, maybe, that otherwise would feel as if it was missing.

Perhaps one of the most challenging things that can happen to us as magicians is when we realize that we’ve slipped into a state of mind like this with regard to our magick. We can quite possibly fall into a relationship with magic where, instead of it becoming the means to realize and fulfil our desires and motivations, instead it becomes an impediment to them. We end up doing magick as a comfort, a form of consolation. The rituals of our magick cease being a means of experiencing something but become subtly, instead, a means of not experiencing something.

If we find ourselves scrolling endlessly, aimlessly, disinterestedly through our social media, I think it’s true to say that although we may not feel we’re benefiting much from that, somebody is. The owners of these platforms are profiting from our distraction. Suppose we imagine ourselves back to the days of the Buddha, and we think of one of these brahmins or ascetics that the Buddha described, who’s overly preoccupied with their headbands or their fancy stick. What would the impacts of that have been? If someone had lost their motivation or was getting overly interested or distracted by something or other, then the impact of that is likely to rebound upon the person themselves and their immediate family, community, and maybe – back then – the community would have been a far more powerful corrective than it is today to help that person motivate themselves onto a more productive track.

Fisher makes the point that the nature of education has changed down the years and, these days, students are regarded as consumers of education. The way educational bodies are funded, they can’t afford to exclude students or fail students because then they won’t receive any funds for them. So, students are aware that they can’t fail the course that they’re on. In that case, where’s the incentive to focus in the classroom when you could be snacking, or scrolling through your social media, or listening to music on headphones?

The students are consumers in a marketplace of education. There’s not an educational community there, as such. The power of teachers like Fisher is eroded, negated, and there are parties – invisible, absent parties – who are profiting from the students, regardless of whether they pass or fail.

What Fisher was seeing in his students he felt was partly natural teenage languor, but also something more than that: an attempt at resistance.

“They know things are bad,” writes Fisher, “but more than that, they know that they can’t do anything about it” (Fisher 2009: 21).

In a control society, you’re supposed to motivate yourself. You’re supposed to apply your own punishments to yourself. But if you don’t want to go in the direction that the control society is pointing you – what do you do? It seems the only alternative is to resist motivation, and desist from punishing yourself, and it’s this that perhaps accounts for the strange paradoxes of depressive hedonia. On the one hand, we find ourselves restlessly seeking pleasure. On the other hand, that pleasure never arrives, because we’re not going where we want to go.

“What must be discovered,” suggests Fisher, “is a way out of the motivation / demotivation binary, so that disidentification from the control program registers as something other than dejected apathy” (Fisher 2009: 30).

It seems that depressive hedonia can be a form of resistance, but it’s an immobilizing one. It’s one in which we put our desire on ice. It’s my suspicion that depressive hedonia at the moment is endemic. Depressive hedonia, I’ve suggested, is what arises when we feel we’re confronted with a situation to which there’s no alternative. In a control society, as ours seems increasingly set on becoming, the source of the discipline and punishments that’s regulating our behaviour as consumers, supposedly comes from inside ourselves, so if we’re being forced in a direction that we don’t want to go in, even though it’s presented as the only alternative, then the only option we have is to resist disciplining and punishing ourselves.

Within a kind of outer case of depression there’s an inner sanctuary of a kind of addiction, where we resist motivating ourselves to do something we don’t want to do by resorting to pleasure instead. But that pleasure never really delivers satisfaction, because it wasn’t our choice to go seeking it in the first place.

More of us, I think, and for more of the time: we’re being confronted with a situation like this. Take the ecological crisis, for example. The overriding aim of capitalism is to make a profit, so it just keeps on consuming resources. Capitalism is the cause of the current ecological crisis, yet we’re told there’s no alternative to this. The solution, we’re reassured, is more capitalism, using green technologies. Somehow we, as consumers, will need to discipline ourselves and consume more wisely. Therefore, if the planet gets trashed, that’s because of the choices we’ve made as consumers within capitalism. So, again, this structure, this idea of a course we have to pursue, because there’s no alternative, and yet we are the ones supposedly responsible for making that course of action we haven’t chosen work. If it doesn’t work, it’ll be our fault for not doing the recycling, or choosing a green energy provider.

It’s there again, maybe, that same structure, in the effects of the covid pandemic. We’re assured we have to get back to normal. There’s no alternative to this, even though one of the things the pandemic has done is expose the inequalities in our society, and there are many of us, I think, who would dearly love not to get back to normal, not to go back to how things were. So, we get our jabs from the big pharma companies – and those, of course, are effective to a considerable degree – and then: that’s it. That’s done. It’s up to us now to get back to normal. It’s up to us to find a way to do precisely what we were doing before.

I think that during the pandemic I did a lot of mourning, a lot of grieving. I’m still doing it, I think. Over the past couple of years I’ve been battling constantly against depressive hedonia. It was interesting how, after the first lockdown, my magical practice seemed to dissolve almost completely away. I wasn’t even meditating. Sometimes weeks would go without me sitting. What I found myself doing instead was distracting myself with work, drink, food, watching crap on television, listening to occult podcasts, making occult podcasts…

I’m still struggling with the idea of going back to normal, because I never liked normal anyway. The thing about the pandemic was it exposed how shit normal really was. It’s been a huge struggle getting my magical practice, my spiritual practice, back online, and it’s an ongoing struggle. Over the past couple of years, I would start getting things back again, only for it to collapse, and having to do it again and again.

It’s felt like the last two years have been a kind of bouncing along the bottom. One of the things about depression is it can feel as if all the meaning has drained out of life, but the pernicious thing about depressive hedonia is we keep finding things that we can disappear into, that do seem to offer some sort of refuge, a kind of meaning, a kind of pleasure. Yet, as we’ve seen, these never provide full satisfaction. We can perhaps find ourselves constantly realizing that we’re putting our energy and our interest into the wrong thing. That perhaps accounts for this feeling that I described: “bouncing along the bottom”. We feel that we’re back on track only to discover that actually we’re just hiding away in a different refuge.

We’re not immune to this as magicians. In fact, I wonder if we’re perhaps even more vulnerable to it because, of course, we’ve got this wonderful treasury of practices, traditions, yet these – as I was suggesting earlier – can function themselves just as further forms of refuge. A subtle, maybe imperceptible shift can occur in our practice where we’re no longer practising magick in order to change our reality, but we find ourselves practising magick because we can’t change our reality.

One of the forms I noticed this taking in my own life – and it was really quite strange when I noticed it – had to do with exercise. That was another thing that dropped away during the pandemic. Suddenly I just lost all impulse to go out running. One day it dawned on me that the feeling behind this was: if I got fit again, then it would mean that it would be easier for me to return to the kind of routine I had before the pandemic started. It was odd. It felt almost as if my body wasn’t mine. It felt almost as if being fit didn’t benefit me. I was feeling as if going out for a run was doing Boris Johnson more good than it was doing me. It was really strange! Of course, Boris Johnson doesn’t care whether I go out for a run or not, but I think that feeling was pointing to a subtle shift that had taken place: that where my will was, where my desire was, was not so much in the place of wanting or creating something for myself, but wanting to deny or destroy something good in myself so that it couldn’t be taken away by something outside of me. It was indeed an impulse that was trying to mount some kind of resistance but, like all psychological defences, these tend to bolster the ego, fortify it, whereas in magical and spiritual practice, of course, what we’re generally looking to do is to open it up, loosen it, increase its participation in something beyond ourselves.

The thing is, I think, misery, pessimism, gloominess, this too can be an object of addiction. There is a grim delight in revelling, enshrouding oneself in the horribleness of things. Suffering is something that we don’t always want to get away from, but it too can also offer a form of retreat.

First off, I think it’s important to appreciate that element in depressive hedonia which is a form of resistance, an attempt to hold steady and fight back to some degree. It’s a response to feeling forced down a path that one doesn’t want to go down, and that needs to be recognized and given some respect and compassion.

Over the months, somehow I managed to start up again and struggled to maintain a daily magical practice, but it was tough, and it was also very tenuous. Sometimes I’d lapse again and have to start again from scratch. It was a struggle and it was difficult, and this is another thing that it’s important to acknowledge and respect: difficulty and struggle is part of the magical path. It’s what we sign up for. The cost of doing something that’s difficult and that not many people do is that probably inevitably you’re going to get lost and stuck at times. It reminds me of something Fisher himself says. He wrote:

Some students want Nietzsche in the same way that they want a hamburger; they fail to grasp – and the logic of the consumer system encourages this misapprehension – that the indigestibility, the difficulty is Nietzsche. (Fisher 2009: 24)

He was noticing his students wanting to be able to understand something that was complicated, abstruse, difficult, and then becoming distressed when they found that it wasn’t easy. But, of course, the fact that they are becoming distressed and aren’t finding it easy shows that they’re on the right track! They’re actually engaging with Nietzsche, or whatever it is that they want to understand. The same is true of the magical path, and probably it’s true also of any serious endeavour that we undertake. Struggle is a sign of progress, not of failure.

So, eventually, I had some kind of daily magical practice up and running, and one of the things I decided to add into that was a daily divination using the tarot. One of the things that quickly became interesting was how frequently certain cards seemed to be turning up, but not necessarily the ones I might have expected.

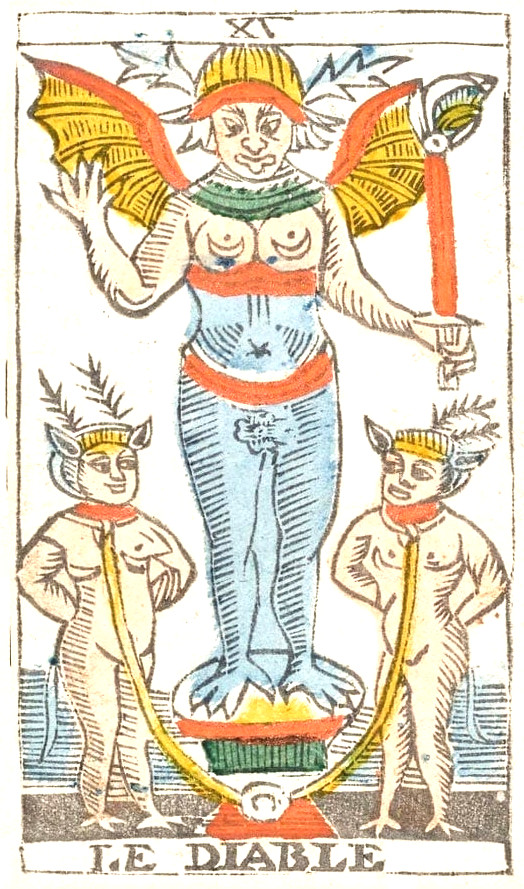

If we think of the major arcana and which of those cards might best represent the state of depressive hedonia, it’s got to be The Devil, hasn’t it? The devil is often taken to represent ideas such as addiction, restriction, duality, materialism, overwhelming instincts or drives; the state of being dominated by some sort of force that it’s impossible to overcome. But that wasn’t the one I noticed turning up when I did a three-card spread every morning over the weeks, and that’s interesting because if The Devil had been the card turning up, I probably would simply have assumed that I knew what it represented – that it represented simply the feelings of depression that I was battling against.

Instead, the card that kept turning up, again and again, was the card that precedes The Devil in the sequence of the major arcana: number XIV, Temperance. And each time I noticed it appearing, it was never the right way up. It was always Temperance upside down. Because it felt a little out of place and its meaning seemed a little difficult to grasp, that was what caused me to reflect more deeply on what this card could possibly be pointing to and what it might represent.

I started getting interested in the tarot for the first time when I was about thirteen years old, and I remember reading at the time a book – I can’t remember which one – in which there was something that always stayed with me. The person who wrote this book suggested that in the major arcana of the tarot what we have there is a pictorial representation of the nature of change itself. This person was arguing that in a universe where the only thing that doesn’t change is change, then a map of what change is and how it works would be something that offered dependable information. They seemed to be making the case that all oracles to some extent work on this basis. Every oracle – most obviously, most clearly, I think, the I Ching, but any oracle – the runes, the tarot, the different patterns of dots that you get in geomancy – what it is that all these pictorial oracles present is a model of the way change works in a form that we can consult.

So, thinking about that sequence in which Temperance and The Devil appear in the major arcana, we’ve got number XIII Death, the tarot card that represents sudden, dramatic change; and then following that comes Temperance, which is about finding equilibrium; and then number XV, The Devil, becoming locked in dominating, restrictive, influences; and then after The Devil, number XVI, The Tower, which is all about the status quo being blown away and a new perspective revealing itself, something hitherto inconceivable blowing everything away.

Those are just a few cards in the sequence, of course, and I’ll leave you to think about how or whether the other major arcana feed into a map of the nature of change, but just taking those few cards, numbers XIII, XIV, XV, and XVI, maybe it is possible to see how the processes of change itself are mirrored in that sequence.

Thinking about historical events, very often there will be a sudden revolutionary change that sweeps things away, in the manner of the Death card, and when that happens there is often a moment when equilibrium is restored, and there’s the possibility of some new kind of harmony to take shape. But often what generally happens after revolutions – just thinking of the French Revolution of 1789, or the English Civil War in the seventeenth century – yes, radical change comes and there is a moment of euphoria when a new harmony seems to have installed itself upon Earth, only for that to be followed by some new form of oppression, whether that’s Napoleon or Oliver Cromwell, both of those perhaps acting to some extent as the figure of The Devil in the tarot suggests. Then, in due course, The Lightning-Struck Tower makes its influence felt, where the actual outcome of all this revolutionary change finally comes home to roost, but in a form that couldn’t have been predicted at the beginning; that’s entirely from out of the blue.

It’s an interesting idea to play with, maybe, and perhaps to some extent the covid pandemic we can take as the Death card: sudden change. Maybe those archetypal images of Temperance and The Devil are both in play at the moment, some of us seeing opportunities for a new harmony; some of us seeing new forms of oppression taking root in the world. But I think it’s almost certainly the case that the upshot will indeed be The Lightning-Struck Tower, a change of a higher order altogether that no one will probably have seen coming.

So, The Devil is maybe a good depiction of the state of depressive hedonia, but the card that kept turning up was Temperance, and it was reversed. The sense I got from that was maybe what I was being shown was not so much what was present, but perhaps something that had not yet come into being. So, what I did is what I’d recommend anybody to do in this sort of situation, which is to take a look at the book Meditations on the Tarot.

This book is a series of esoteric Christian essays on the twenty-two major arcana. It was published anonymously in around 1967, and although we do know who the author is, it was clear that the author wanted to be anonymous, so the polite thing to do, I think, is always to refer to them as “Anonymous”. But suffice it to say that the author was an anthroposophist, a follower of Rudolf Steiner, although he eventually split from the anthroposophy movement and found a home apparently in something more along the lines of Catholic mysticism.

As I read through Anonymous’ chapter on the fourteenth arcanum, Temperance, which is rather lengthy and quite dense, and does contain a few digressions into points of Christian doctrine, some really amazing insights seemed to jump out at me.

Whereas arcanum XV, The Devil, shows us what depressive hedonia is, it does indeed seem as if in the idea of Temperance there’s perhaps something really incisive on how to deal with depression and depressive hedonia.

Anonymous starts off with the basics. So, what we have in this card is the figure of a winged angel and the angel’s gaze and our attention is being drawn to the two cups that he or she is holding, and between which liquid is flowing. But there’s something quite odd going on here, because the liquid is kind of floating in the air. Something otherworldly is happening here, something that defies earthly gravity.

To delve deeper into the question of what an angel is, and what this particular angel might be doing, Anonymous takes up a couple of ideas from St Bernard: the idea of “the divine image” and “the divine likeness”. These both come out of Catholic theology. The divine image is that part of us that is made in the image of God, which is in some sense eternal and partakes of the nature of God. But the divine likeness is that other aspect of human nature, which in a Catholic context is regarded as fallen, as being prone to sin and degradation.

Anonymous suggests that the angel in the Temperance card is not just any old angel, but the guardian angel: an angel that every human being has watching over them. He suggests that what the function of the holy guardian angel is, is to act as the ally of the divine image.

So, the guardian angel is a spiritual being that serves and strengthens the impact of the divine image upon how the human being expresses itself on Earth. Now, the relationship between a guardian angel and its human might not be as straightforward as it seems at first. Anonymous points out that although our angel protects us, it doesn’t shield us from temptation or difficulty. As I was suggesting earlier, difficulty, struggle are signs of progress, not a failure. It’s out of difficulty and struggle that growth can come, so our angel won’t protect us from that. This means that we can’t look to our angel as a means of salvation from difficulty. If we’re depressed, then the angel is not going to take that away. The angel is not a means of avoiding depression but, instead, the depression is working as a signal that we need our angel, that we need its protection, but evidently not in a straightforward sense.

Another aspect of the function of the guardian angel that Anonymous mentions is the way that the angel screens us from the divine. When we mess up, when we do wrong, that can call down upon us all sorts of unpleasant consequences. The angel doesn’t punish us in the way that we might conceive of God as punishing us (or reality itself inflicting upon us the consequences of our behaviours). The angel always defends us against the divine, a bit like a mother defends their child. Even when the child has done something manifestly wrong, the mother will still protect her child, even whilst acknowledging that wrongdoing has been done. Anonymous suggests that this is why angels often take a feminine form although, of course, they’re beyond gender.

Again, a bit like a loving, caring mother, the angel leaves us alone to do our own thing. If we’re not in need of or calling upon our angel, then it doesn’t come. It leaves us alone. You have to be in need; you have to be calling out to it, in order to benefit from its presence. So, the angel is the representative, the ally of the divine image in the human, and it’s there to watch over that other aspect, the fallible part, the divine likeness in the human. If you remember, the divine likeness is the aspect of us that lives on Earth, the earthly aspect that’s prone to evil and messing things up, and does the best it can.

Anonymous seems to be suggesting that this is what we see in the Temperance card. The water flowing between the two cups represents circulation, the functioning, the activity of the human being: the divine likeness. The angel is standing there, watching over, carefully concentrating upon this circulatory process between the two cups. The angel is the protective representative to us of the divine spark, and they’re watching over, regulating, carefully monitoring the everyday, functioning, living aspect of us which needs to be kept in balance, needs to be carefully maintained. That’s why, Anonymous suggests, that the angel in this card takes the name Temperance: that balancing, regulating, homeostatic aspect is one of the chief characteristics of what it takes to keep going in everyday life.

So, the divine image and the divine likeness are both parts of being human, and they both meet in the human being. Anonymous suggests that there is an experience associated with this meeting, this contact between them, and he describes this as a kind of “inner weeping”, inner crying. This is how he describes it:

The fact that there are tears of sorrow, joy, admiration, compassion, tenderness, etc., signifies that tears are produced by the intensity of the inner life. They flow – whether inwardly or outwardly is not important – when the soul, moved by the spirit or by the outer world, experiences a higher degree of intensity in its inner life than is customary. The soul who cries is therefore more living and therefore fresher and younger than when it does not cry. (Anonymous 2002: 388)

Tears come from emotional intensity. Anonymous suggests that the liquid that we can see flowing in the Temperance card is tears. The two cups represent the divine image and the divine likeness, and the liquid flowing between them are tears of emotional intensity, tears of inspiration.

Consider this in relation to what we’ve talked about, with regard to depressive hedonia. When we’re depressed we lose any sense of emotional intensity, and we find our attention leaking away into things that don’t deserve it. I was struck by how, in contrast to that sense I’d noticed in myself of the idea of somebody watching over me who was making me do something deathly that I didn’t want to do, here, in the Temperance card, we’ve got the exact opposite: there’s an angel watching over us who cares deeply about us, and is regulating us in our best interests, and is actually raising up our emotional intensity by making the tears flow between the two cups.

What Anonymous is directing us to in the Temperance card is an image of inspiration, emotional aliveness, and intensity. Depression, depressive hedonia, as we’ve explored it here, seems in contrast to this like the shadow side of that, almost like a dark inverse of what’s going on in this card. What is lacking, what is needed in depression is inspiration. Anonymous is drawing on some of Rudolf Steiner’s ideas here. Steiner had this notion of the three spiritual faculties, which he listed as: imagination, inspiration, and intuition.

I’m not going into that too much here, except to say that a way to approach these is to see them as analogous to our everyday faculties of perception, emotion, and thinking. So, imagination is the spiritual counterpart of perception, because through imagination we get to perceive things that don’t exist. Likewise, inspiration is the spiritual counterpart of emotion, because through inspiration we have feelings for things that don’t exist, or don’t yet exist. And intuition is the spiritual counterpart of thinking, because it allows us to recognize things that otherwise we would have absolutely no basis for being able to think about them.

What’s being depicted in the Temperance card, Anonymous suggests, is the spiritual faculty of inspiration, and what the tarot seemed to be showing me personally was that this was missing. This was what was needed. The antidote to depression is inspiration.

Now, as Anonymous goes on to discuss, just knowing that, just recognizing that isn’t an end to the problem. Inspiration is a tricky thing to arrive at. You can just wait for it to arrive, but in all likelihood you’re going to be waiting for a long time. You have to do something to get inspired. Yet, if you’re doing something then there’s the possibility that we’re getting too involved in that, rather than letting something come to us, which is an essential part of what inspiration is: something comes to us.

Anonymous points out that to put ourselves in the way of receiving inspiration, you kind of have to be active and passive at the same time. We have to be humble, on the one hand; we have to put our egos out of the way so we can open up and receive something. But on the other hand we’ve got to be keen, we’ve got to be willing, we’ve got to be energized and up for doing the work, when whatever it is finally comes along.

Again, it’s striking and curious how depressive hedonia is the exact mirror image or shadow of this. We’re not willing to give up our energy because it feels as if what’s being demanded of us is something that we don’t want to do, and we’re not humble we’re not compliant. In this situation we’re defiant, we’re resistant, we’re taking a stand against the power that’s being wielded over us, it feels. It’s as if the whole thing needs to be flipped around somehow

With regards to how that’s done, Anonymous draws our attention to how children behave. On the one hand, children are aware that they don’t know as much about the world as adults do, but on the other hand they’re not afraid to ask about things; they’re often not afraid to want to know, and he suggests that we can use this as the basis of our model for how we go about gaining inspiration.

“Dear Unknown Friend,” he says,

say to yourself that you know nothing, and at the same time say to yourself that you are able to know everything, and – armed with this healthy humility and this healthy presumption of children – immerse yourself in the pure and strengthening element […] of inspiration. (Anonymous 2002: 395)

This, of course, is something that magick enables us to do. On the one hand, it confronts us with our limitations as human beings, and at the same time – on the other hand – it confronts us with what we’re capable of: connection with the divine through that spark of the divine that we carry in ourselves. That simultaneous humility and presumption are both there.

Anything can become a crutch, a hiding-place, when we’re depressed, and magick is no exception to that. Sometimes it becomes a bit of a comfort blanket. The aim of the magician has been described famously as being “to dare, to will, and to know”, and perhaps when these are more apparent, then we can be more confident that our magick is on track.

So: depression, nihilism, boredom, desperation. These are states that can be real magick-killers. Depressive hedonia, as we’ve seen, is something that is perhaps really pervasive at the moment, and has a structure to it that can really lock us into these states and make them difficult to escape from.

The psychoanalyst Adam Phillips famously described boredom as “the desire for a desire” (Phillips 2017). Boredom comes about when we find ourselves in a paradoxical state where we want to want something enough in order for us to find ourselves doing something. I think depression’s similar in some ways. I think depression also, in a sense, is the desire for a desire, but in depression – for whatever reason –whether it’s something inward or outward – there’s a heightened hopelessness, a despair that desire is ever going to come along. In depression, desire itself feels futile, even if it were to arise.

Inspiration, as depicted in arcanum XIV Temperance in the tarot, and as revealed to me by the tarot and by Anonymous as the antidote to depression: this could be described in similar terms. Inspiration is not the desire for a desire, but perhaps the desire of a desire.

Boredom and depression, the desire for a desire, is a negative feedback loop. The very act of wanting is destroying the prospect of attaining. But inspiration as the desire of a desire is the opposite: a positive feedback loop. We want to desire, and we are already desiring, and in that act we actually generate more of what we already have. Out of this kind of desire comes no sense of lack at all, but a plenitude.

This is, I think, what inspiration really feels like, when it comes.

References

Anonymous (2002). Meditations on the Tarot, translated by Robert Powell. New York: Tarcher.

Mark Fisher (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Alresford: Zero.

Gabor Maté (2018). In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. London: Vermilion.

Adam Phillips (2017). On Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored. London: Faber & Faber.